How Preservation Happens (and Doesn’t) in New Mexico: A Conversation with Steven Moffson

On the Gaps Between Recognition and Protection in New Mexico’s Historic Landscape and Earthen Architecture

Introduction

When I first set out to understand how preservation works in New Mexico, I thought I’d begin with the trail. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro—the centuries-old trade route connecting Mexico City to northern New Mexico—seemed like the perfect thread to follow. I imagined that along its 400‑mile stretch within the state, there would be detailed records of buildings, towns, and the stories etched into adobe walls. What I found instead was a map with gaps.

To better understand those gaps, I sat down with Steven M. Moffson, the State and National Register Coordinator for the Historic Preservation Division of New Mexico. He is one of the people responsible for reviewing, documenting, and nominating historic places to the National Register—a process that gives a site recognition, but not necessarily protection.

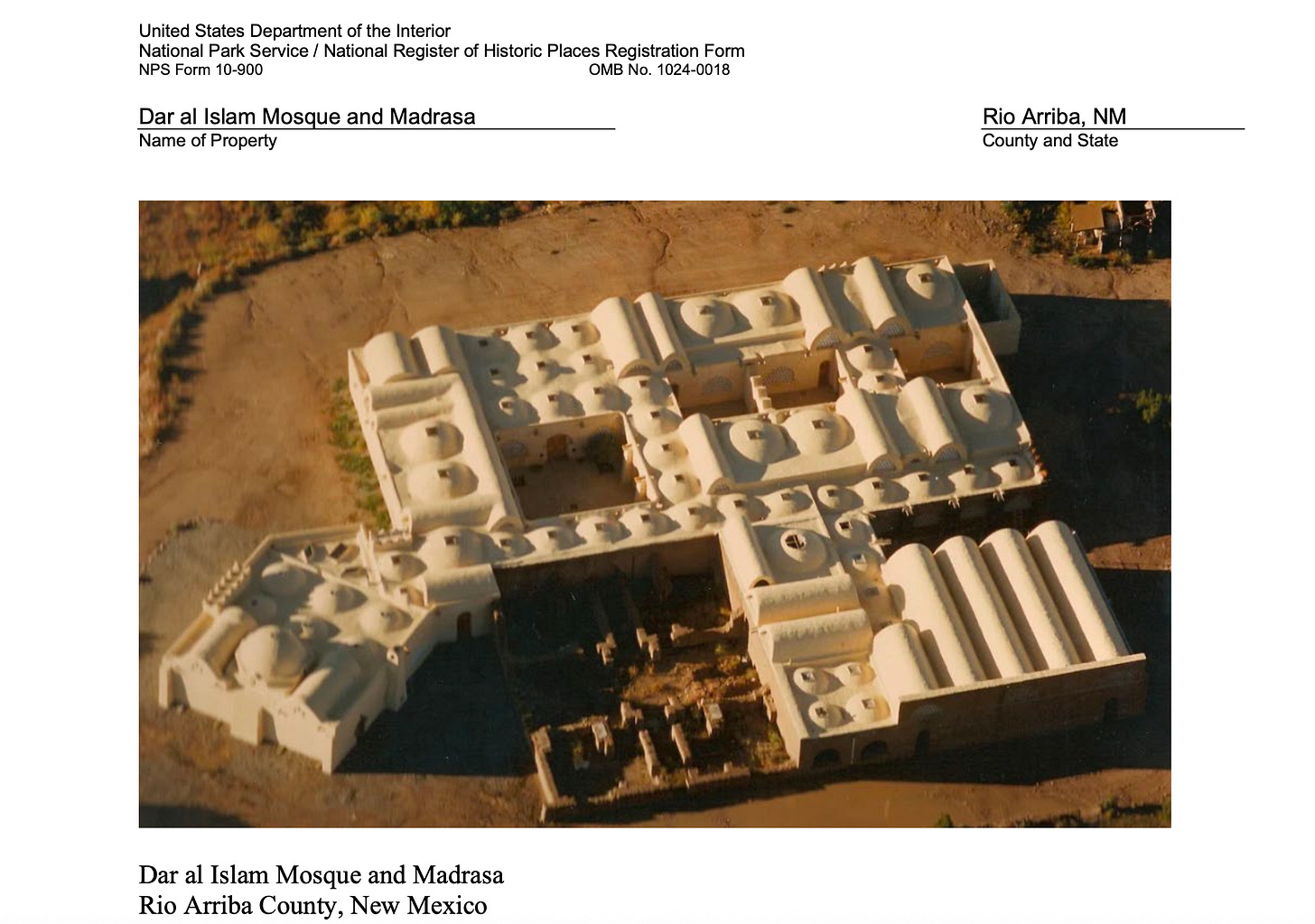

In this wide-ranging and generous conversation, we discuss the fragmented documentation of El Camino Real, adobe and sod construction, puddled earth traditions, the political frameworks of preservation, and what it means to nominate buildings for national versus state recognition. We also explore how preservation efforts can obscure or perform history—especially in Santa Fe—and how the National Register program grew from humble, often flawed beginnings in the 1960s to become the system we have today. From the enduring walls of the Hubbell House to the controversy surrounding the unlisted Dar al-Islam mosque, this conversation opens up the gaps between buildings, policy, and memory.

Interview

Mulham Alkharboutli (MA): Let’s begin with El Camino Real. You mentioned that although it spans over 400 miles in New Mexico, the documentation focuses mostly on the trail itself—not the buildings or villages along it?

Steven Moffson (SM): That’s right. What we’ve listed are trail sections—some just a few hundred feet, others a few miles—but they mostly avoid villages. The nominations focus on the trail’s physical corridor, often rural and archaeological in nature, not the settlements.

So, while the trail itself might be documented, buildings or communities along it usually aren’t—unless they were nominated independently. If you’re interested in a specific building, you need to already know it exists and hope it was listed on its own.

People often assume that trail and village records are integrated, but in practice, we’ve treated them as separate. Most Camino Real listings are narrow in scope and don’t include surrounding architecture or communities.

MA: So there’s no comprehensive architectural survey of Camino-era buildings along the route?

SM: That’s correct—there’s no single, comprehensive architectural survey that documents buildings specifically associated with El Camino Real. What we have are separate listings: some cover segments of the trail itself, and others cover individual buildings, but the two are rarely connected in a formal way. The trail nominations are usually focused on the physical corridor—often as archaeological sites—rather than on the built environment along its path.

If a Camino-era building was listed, it was likely nominated independently, without explicit reference to its relationship to the trail. That means if you're studying Camino-related architecture, you'd need to identify each structure individually and hope the documentation exists. There’s no centralized database that ties these resources together. It’s a major gap in how the Camino’s historical landscape has been preserved and understood.

MA: What about the quality of documentation in these listings over time?

SM: The quality of early documentation—especially from the late 1960s and 70s—was pretty poor. When the National Register was first created in 1966, the focus was on speed. People were trying to list as many important properties as quickly as possible, which meant the nominations were often very minimal. Many didn’t include site plans, had poor-quality or missing photographs, and offered little analysis or historical context.

Ironically, that means some of the most important buildings in New Mexico were among the least well-documented. The urgency of those early years led to major gaps in the record.

MA: When did that shift?

SM: The shift really began in the 1980s. That’s when the National Register program started requiring more robust documentation—things like site maps, architectural drawings, and historical context became standard. There was a push toward consistency and depth, though in practice, the quality can still vary depending on who’s preparing the nomination and how much time or funding is available.

MA: Are there particular buildings along the Camino you think are essential to see?

SM: Definitely the Hubbell House near Albuquerque. It stands out not only for its preserved adobe form but also because it contains an exposed section of terrón construction—blocks of sod and grass, which are much rarer than adobe. You can actually view this through a plexiglass window installed in the wall, which makes it a valuable educational site. The house is open to the public, serves as a museum, and is among the best-documented Camino-related structures we have.

MA: What is terrón exactly, and how common is it?

SM: Terrón is essentially cut turf—blocks of thick grass and earth sliced directly from the ground and stacked like bricks. It’s a method more closely tied to the landscape, requiring no molds or forms like adobe does. Although it’s much less common than adobe brick, it was still used historically in certain areas, especially where materials like clay or straw were less accessible. Today, very few structures survive with exposed terrón, which makes the Hubbell House especially important. It has a rare plexiglass section where you can actually see the terrón inside the wall—a tangible example of this technique preserved and interpreted for the public.

MA: What about puddled earth, or other non-brick techniques?

SM: Puddled adobe, or puddled earth, was used extensively by Indigenous Pueblo communities before the arrival of the Spanish. Instead of shaping blocks, builders would lay down thick layers of wet mud by hand, forming walls layer by layer. You can actually see the horizontal striations it left behind in historic Pueblo structures. This method required deep knowledge of the material and was remarkably durable.

It’s a critical but often forgotten part of Southwestern building history. When people think of adobe today, they usually imagine sun-dried bricks, but that system was introduced and standardized by the Spanish. The Puebloans had already developed their own sophisticated, large-scale earthen architecture long before that—without needing molds, bricks, or foreign tools.

MA: And the Dar al-Islam Mosque in Abiquiú?

SM: Architecturally, it’s one of the most extraordinary adobe structures in the region. It features domes, arches, and vaults—elements rarely seen in traditional New Mexican adobe. The design was heavily influenced by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy and combines North African aesthetics with local earthen materials.

We actually prepared a nomination for the National Register, but the board overseeing the mosque declined to move forward. They were concerned that a listing might come with design or maintenance restrictions, even though legally, the National Register imposes no such constraints on private property. I wrote a letter clarifying the legal protections and emphasized that they’d retain full control, but the board remained hesitant and ultimately said no. It was a real loss from a preservation standpoint, because the building is not only stunning, but also deeply unique in the New Mexican context.

MA: So just to clarify—being on the National Register doesn’t limit what a private owner can do?

SM: Correct. In the U.S., private property rights are extremely important. The National Register of Historic Places is an honorific listing—it recognizes a property's historical value, but it doesn’t impose restrictions on private owners. That means if your building is listed, you can still paint it, remodel it, or even demolish it if you choose.

The National Register itself is not a regulatory tool. Any design or preservation restrictions would only come from local ordinances, like those in Santa Fe or Taos, where there are formal review boards and permitting processes for exterior changes. But those are local-level protections, not part of the national listing system.

MA: And what happens if a building is significantly altered?

SM: Technically, if a property is altered too much—say it loses the features that made it historically significant—or if it's destroyed, it can be removed from the National Register. That process is called delisting.

But in practice, it’s extremely rare. I’ve been doing this work in New Mexico for over a decade, and we haven’t removed a single property from the Register in that time. Our focus is on recognizing and documenting historic places, not on policing them. Most changes, even substantial ones, don’t automatically trigger removal unless they fundamentally erase what made the building significant in the first place.

MA: What about state vs. national vs. local registers?

SM: We maintain the State Register of Cultural Properties here in New Mexico, which functions very similarly to the National Register but is administered at the state level. It uses almost identical criteria and allows us to recognize and track historic resources that may not rise to the national level but are still locally or regionally significant.

Above the National Register is the National Historic Landmark (NHL) program. That’s a much more selective tier—it’s reserved for properties of national significance, and the documentation and review process is far more rigorous.

And then above that, you have National Historic Sites, which are formally designated and managed by the National Park Service. Those often come with active stewardship, interpretation, and federal protection because of their exceptional public value.

MA: Are the trail segments you listed at the state or national level?

SM: Mostly at the national level. We've listed about 20 segments of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro in the National Register of Historic Places. These listings focus primarily on the physical remnants of the trail itself—not structures or nearby settlements.

Some of the listed segments pass through significant archaeological zones, like the Jornada del Muerto, a stretch of desert that travelers historically crossed without access to water. These areas don’t have any built structures—just compacted trails created through repeated use over centuries. Because of the archaeological sensitivity, we sometimes have to redact parts of those listings—covering exact locations or map data to protect them from looting or disturbance.

MA: What about documentation quality in southern towns like Doña Ana?

SM: That’s a really important example. Doña Ana has some highly significant adobe homes—structures that speak directly to the region’s colonial and territorial history. But unfortunately, much of the preservation that’s taken place there hasn’t always followed traditional practices. In many cases, restoration efforts used cement stucco instead of mud plaster, which has serious consequences for adobe.

Cement doesn’t allow the walls to breathe—it traps moisture inside, which accelerates deterioration of the underlying earthen material. Over time, this causes adobe walls to crack, erode, or collapse from within, even if they appear intact from the outside. As a result, we've lost a lot of material integrity in Doña Ana, not because of neglect, but because of well-intended but technically harmful interventions.

It’s a preservation challenge we see across many rural communities: the historic buildings are there, but the documentation and conservation methods haven’t always kept pace with best practices. Without proper training or oversight, even “restoration” can sometimes lead to irreversible damage.

MA: Do you find that the railroad changed vernacular forms?

SM: Absolutely. The arrival of the railroad in 1880 was a major turning point. It brought with it milled lumber, which wasn’t locally available before. That allowed builders to construct pitched roofs instead of the traditional flat ones common in adobe architecture. But it wasn’t just about materials—it also reflected changing aesthetic values.

Pitched roofs were seen as modern and fashionable, especially in northern New Mexico where shedding snow was also a practical concern. So you start seeing hybrid buildings: adobe walls built the traditional way, but topped with a gabled or framed roof structure. These buildings mark a shift not just in construction, but in identity and aspirations.

MA: Is that why post-1880 adobe architecture is underrepresented in scholarship?

SM: Yes, exactly. There’s a major gap in documentation and scholarship covering the period after 1880. Bainbridge Bunting’s Early Architecture of New Mexico—which is still considered foundational—ends its survey at the point when the railroad arrives.

Since then, no one has done a truly comprehensive study of adobe architecture post-railroad, despite the fact that the material continued to be used extensively. That era includes important transitions—technological, cultural, and stylistic—but it’s been largely overlooked. It's one of the biggest blind spots in our architectural history.

MA: Let’s shift to Santa Fe. You mentioned the city's historic ordinance. What’s your view of how it shapes preservation?

SM: Santa Fe’s ordinance requires buildings to conform to one of several official revival styles—like Pueblo Revival or Territorial Revival—which together fall under what’s called the “Santa Fe Style.” This mandate shapes how new construction and even historic buildings are treated in the city.

The problem is that it often leads to surface-level preservation. A building might be significantly altered or even demolished, but as long as the façade is rebuilt to match one of the approved styles, it’s considered acceptable. So what you end up with is a kind of aesthetic conformity—buildings that look historic but aren’t.

It prioritizes visual harmony over material authenticity, which can erase important historical layers. In that sense, it’s more about maintaining a citywide image than protecting actual heritage fabric.

MA: So there’s a kind of performance of history?

SM: Exactly. What often gets preserved is a curated image of the past—something that looks old or “authentic” but may not be materially or historically accurate. You end up preserving the aesthetic symbol of history, not necessarily the substance of it. That’s especially true in places like Santa Fe, where design guidelines prioritize stylistic uniformity over historic complexity.

MA: I’m also curious about gentrification. Is it a concern in New Mexico?

SM: Not to the extent it is in other states. Santa Fe and Taos are exceptions, where tourism and second-home ownership have definitely driven up housing costs. But in most of New Mexico—particularly rural areas—we’re facing the opposite issue: underinvestment rather than displacement. Communities aren’t being priced out; they’re often struggling to attract the kind of investment needed for basic maintenance and preservation. So while gentrification exists, it’s not the dominant threat here.

MA: Has there been discussion around making preservation more inclusive of intangible heritage or vernacular landscapes?

SM: Yes, and it’s growing—especially in relation to El Camino Real and acequia systems, which are deeply rooted in communal and cultural practice. But our formal tools—like the National Register—aren’t always equipped to capture those intangible or landscape-based values. The system tends to prioritize the tangible, the architectural, the easily measured.

That’s why work like yours—focusing on vernacular, hybrid, or undocumented histories—is so vital. Those are the boundaries we need to push: not just preserving structures, but acknowledging the lived, cultural, and evolving relationships people have with their environment.

MA: Thank you, Steven. This conversation really opened up so much—from the paperwork to the politics to the mud itself.

SM: My pleasure. We need more people asking these questions. Especially people who can see the gaps and help fill them.

If we’re to understand how preservation happens—and doesn’t—in New Mexico, we have to look at more than designations and style codes. We have to look at the places in between, the stories that never made it to the forms. This is only one conversation, but it's part of a larger map we’re still drawing.